In government, we deliver services that meet fundamental human needs: for belonging, for safety, and for human connection. Becoming a citizen of a new country is one of the most emotional life experiences a person will go through and marks the completion of a long journey.

Since joining the Canadian Digital Service earlier this year, I’ve had the opportunity to work with Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) on improving the experience of applying for Canadian citizenship. This blogpost tells the human story behind the service we delivered.

Citizenship ceremony in Vancouver, British Columbia

Designing for equity

Immigrants arriving in Canada face many economic, linguistic, and social barriers in their settlement process. Rates of low income among immigrants continue to be high relative to the Canadian-born population. Achieving the permanence of citizen status lets immigrants settle into life in Canada – to grow their career and provide stability for their families.

Given the disproportionate barriers immigrants already face, how might we design a compassionate service that helps redress this inequity and provide a fair chance to succeed?

Our partners in the client experience branch at IRCC have been leading departmental efforts to bring a user-centred approach to the delivery of services. We wanted to build on this expertise, so we set out to understand more about people’s experiences of the citizenship application process through an extensive research process.

Together we found two major pain points, and set out to fix them.

Citizenship test centre in Ottawa, Ontario

1. Notice to appear

One of the milestones in the citizenship process is a language test. This is an in-person interview with an immigration officer who will assess your knowledge of Canada and whether you have an adequate level of fluency in English or French. The minimum threshold for speaking and listening ability is Level 4, as set by the Canadian Citizenship Act. This policy is designed to make sure new citizens can integrate with Canadian society.

People applying for citizenship come from 23 different countries and speak 190 languages. Non-native speakers sign up for language classes to help improve their skills and spend months fitting studies around their existing life commitments. Given how invested people are in passing the test, you can see why they’d be anxious.

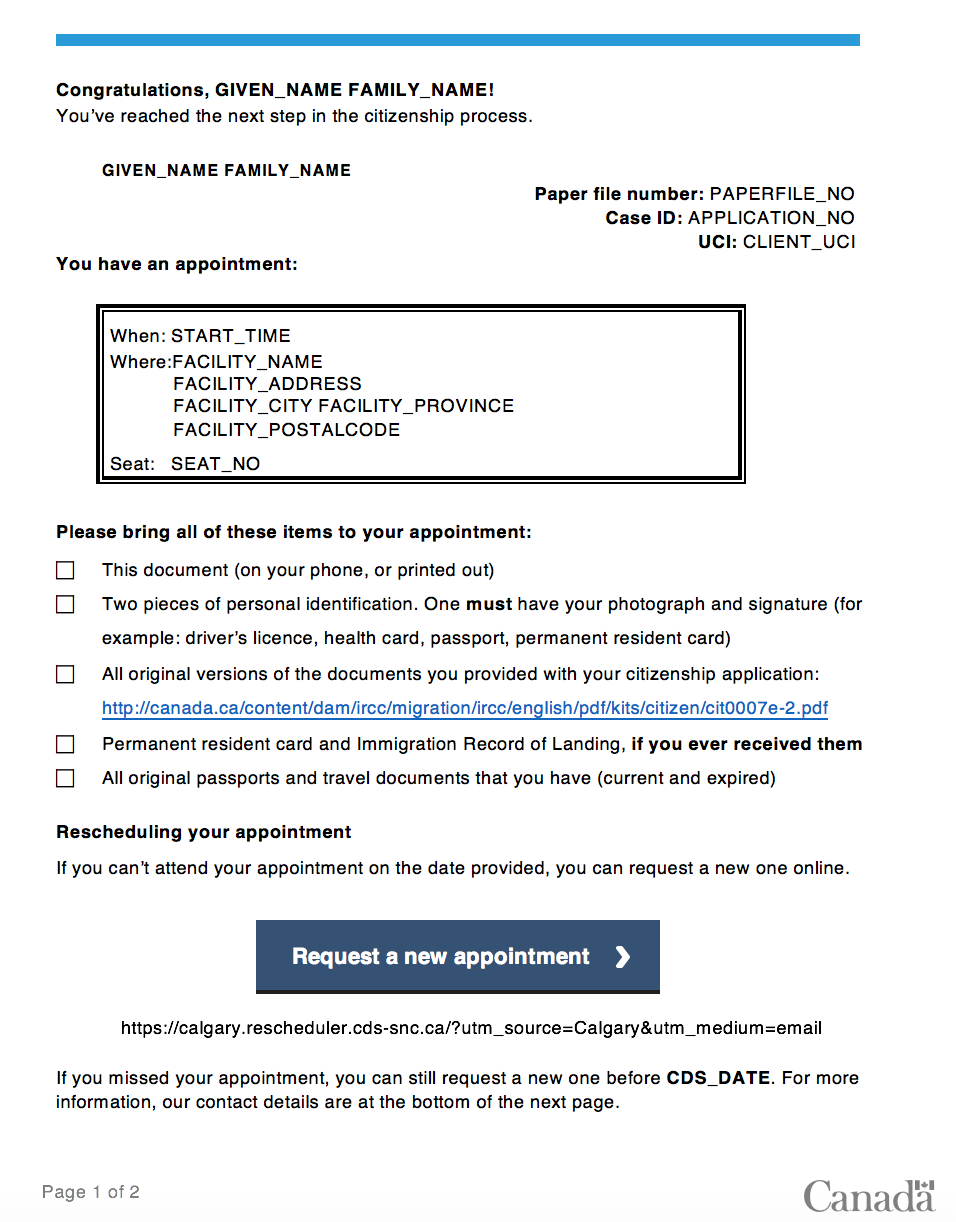

Towards the end of the citizenship process, you get a letter in the mail notifying you about your test date. Here’s what this letter looked like:

Original version of the ‘notice to appear’ letter

Tone: NOTICE TO APPEAR feels like a summons

Language: complex wording based on government policy

Reading level: double that of the average Canadian

For people who read English or French fluently, it’s hard to understand this letter. Now imagine it through the lens of someone whose first language is Mandarin, Hindi, or Arabic. When faced with this challenge, many people turn to their family and friends to help them figure out what the letter is telling them to do.

2. Rescheduling

As an immigrant to Canada, you’re more likely to have time-bound commitments that are difficult and expensive to rearrange:

International business travel

Trips to visit family back home

University classes and exams

Being summoned to a date you haven’t chosen can be stressful. What if your language test clashes with a pre-booked business trip or your final exams?

Before we built our service, here’s what the rescheduling process looked like. You had to write a letter to your local citizenship office. You would explain your reasons and hope to be accommodated. Once you wrote your letter to ask for a different date, it could be months before you heard back. As a result, IRCC received hundreds of calls to their call centre asking for updates and reassurance.

As part of our research, we read hundreds of these letters, many containing highly emotive stories.

‘I really want to attend my test, but it happens to be my daughter’s graduation that day. Would it be possible, to switch to another date?’

Letters from applicants received by the Citizenship office

We heard first hand how scared people were to ask, fearing their whole citizenship application would be thrown out. Some would forego important life events altogether — missing medical appointments or family weddings.

The new service

We set out to make the process smoother for both members of the public and staff. Here’s what we did.

Improved tone, removed ‘government speak’ and used positive language

Clear, simple, and easy to understand

Notify by email for the 95% of people who have internet access. For the 5% who don’t have internet access, notifications are sent as letters in the mail.

Updated version of the ‘notice to appear’ letter

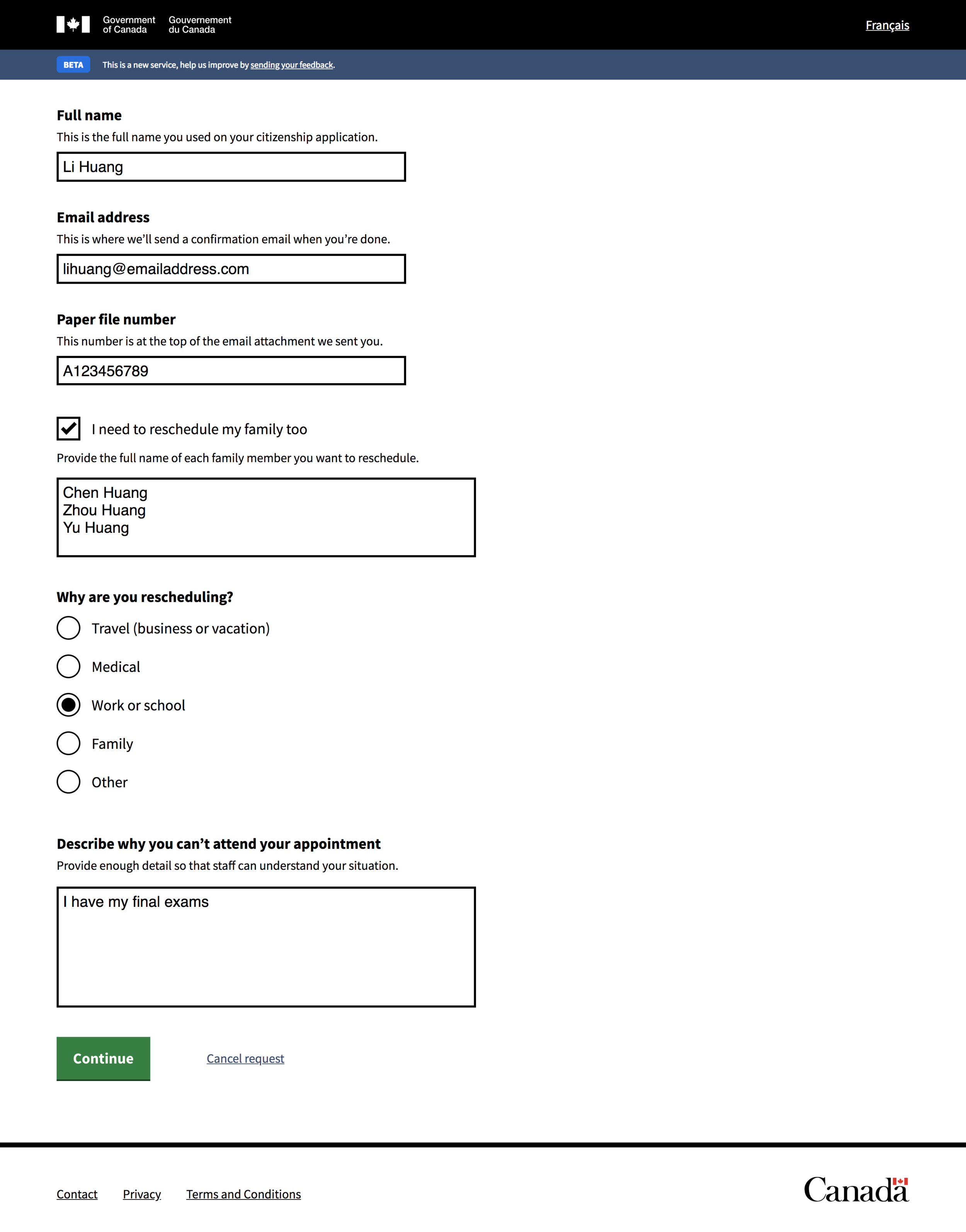

Now, when someone needs to reschedule their test, they follow the link in the email, or phone the call centre. Staff at the call centre are trained to use the online service on their behalf. We worked closely with the legal team at IRCC to get approval for staff to act as proxy, via consent given over the phone. Previously, consent could only be given in writing.

This is particularly helpful because other services can now also work in this way. Having all requests come through the online service also helps local office staff by keeping everything in a single channel — their email inbox.

New online service to reschedule your test

Reassure people their needs are valid, by providing a list of acceptable reasons for needing to reschedule (for example travel, or medical)

Keep families together, by allowing people to reschedule as a group

Immediate confirmation of their request, and clear next steps

Confirmation page

You can try a demo version of the new online service here.

Outcomes

Since going live with the new service in Vancouver this July, we’ve brought Calgary and Montreal onboard with plans for rollout across the rest of Canada. For applicants and staff, having a service designed around their needs delivers a much better experience:

70% fewer paper requests to reschedule

10% to 3% reduction in the number of requests needing follow-up by staff

5% to 10% increase in the number of people asking to reschedule

This last point is particularly important, as tells us people are more confident in the rescheduling process overall. We also anticipate that the number of people who don’t show up to their test, or have to cancel last minute, will decrease as well.

User testing an early version of the online service

Throughout the past seven months, we continually iterated and improved the service based on user research and testing with real people going through the citizenship process. We have reduced the administrative burden on staff, and given 200,000 future Canadians the best possible chance to succeed.

Together with our colleagues at IRCC we’re reshaping the way government works to get closer to what people need. There’s a long way to go but this work has been an important step in moving towards our goal of human-centred services that change lives for the better.